Animal Welfare and Regenerative Agriculture

Alignment of people with food and nutrition isn’t the only food system alignment we care about. We also care about alignment for animals, including their indirect impacts on the environment and world at large.

That means animal welfare and regenerative agriculture are key considerations for how we source our ingredients.

What is animal welfare?

Animal welfare refers to the well-being of non-human animals, including those raised for food production. This spans everything from the foods they eat, to the conditions they’re raised in, to the fresh air they do (or don’t) have access to, to their treatment and care during life, to the methods used for slaughter.

What is regenerative agriculture?

Regenerative agriculture refers to holistic farming and grazing practices designed to keep food production in harmony with the land. This can include the use of cover crops, mulching, no-till farming, livestock integration, rotational grazing, and other techniques that preserve or enhance the surrounding ecosystem.

Collectively, these practices help improve soil health, manage water, and sequester carbon—that is, removing carbon from the air and depositing it back into the soil. Whereas most industrialized farming creates ecological imbalances, regenerative agriculture strives to work with the earth’s natural systems, providing net benefit to the environment.

Although the term “regenerative agriculture” may be new to many people, the practices themselves are extremely old—used by indigenous communities long before industrial agriculture took over.

Impact of factory farming on animals and the environment

Sadly, modern industrial farming practices are driven more by market pressure than by concern for the health and well-being of animals, humans, and the planet at large. In order to cut costs and maximize output, livestock are often confined to small areas, deprived of fresh air and sunlight, given commercial feed instead of grazing on their natural diets, and supplemented with growth hormones and antibiotics—all to produce as much meat as cheaply and efficiently as possible.

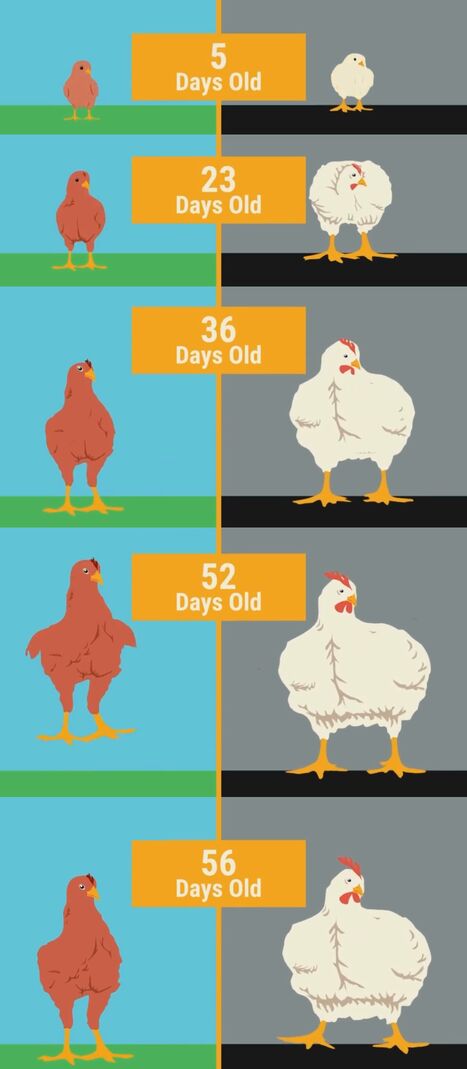

Some livestock, such as broiler chickens, are bred for unnaturally rapid growth and size. In contrast to smaller, slower-growing heritage breeds, these chickens suffer a lifetime of painful and sometimes debilitating health problems, ranging from skeletal deformities to abnormal heart and lung development to difficulty walking. [1]

All of these conditions are diametrically opposed to those of animals in the wild, and make it hard for conventionally raised livestock to thrive.

Not only that, but concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), where over 90% of all livestock in the US is raised, generate enormous concentrations of waste. This waste contaminates local water, harms aquatic ecosystems, reduces air quality, contributes to CO2 emissions, and causes a significant environmental and public health burden.

Likewise, modern industrial farming methods like tilling, monocrops, and the use of chemicals and salt-based fertilizers are damaging to the ecosystem. These modern practices cause a loss of plant and animal biodiversity, pollute the air and water, erode topsoil, require excessive water use, and diminish the nutritional value of food (due to depletion of vitamins and minerals from the soil). This makes industrialized farming harmful for long-term food production, especially on the mass scale currently being used.

Impact of factory farming on human health

Along with impacting livestock and the land, animal welfare and farming practices have consequences for human health.

For example, the overuse of antibiotics among livestock is an issue of global concern. In many parts of the world, antibiotics are distributed to livestock not just to manage disease, but to enhance feed efficiency—that is, the amount of mass gained on a given amount of food. By destroying intestinal bacteria that compete for nutrients, antibiotics allow more of those nutrients to be absorbed by the animal, leading to greater weight gain.

This practice was eventually banned by the European Union in 2006, and made illegal in the USA in 2017. But even when feed efficiency restrictions are in place, antibiotics continue to be massively distributed to factory-farmed livestock—given to healthy animals to prevent infection from sick animals nearby, given to already-diseased animals, and given to entire flocks or herds to prevent disease even when none is currently present (a potential loophole that allows drugs formerly used as growth promoters to still be added to animal feed). The cramped conditions of factory farms encourage infectious microbes to spread more quickly than among pastured animals living in the open air. And because low-welfare livestock have higher stress levels and weaker immune systems, they’re more susceptible to getting sick, leading to a more frequent medical need for antibiotics.

Unfortunately, the use of antibiotics on such a large scale contributes to a major public health concern: the growth of drug-resistant bacteria. This occurs when pathogens become unresponsive to the antibiotics that usually destroy them, making dangerous infections more difficult to treat. Livestock harboring drug-resistant bacteria can remain infected even after antibiotic treatment, in turn passing foodborne illness onto humans (such as from Salmonella and Campylobacter). [2] [3]

What’s more, many of the antibiotics given to livestock are the same ones prescribed to humans. When these drugs cease being effective for animals, they also stop being effective for humans—meaning infections that were once easily treatable can become a much greater health risk. In order to prevent potentially devastating rises in drug-resistant infections, many health agencies are calling for tighter regulations on the use of medically important antibiotics in animals.

Farming practices also impact the healthfulness of meat and plant foods. Feedlot cows, for instance—raised on high-omega-6 grains instead of grazing on grass—produce meat with higher levels of inflammatory fats. This contributes to the already excessive omega-6 intake in the modern human diet, with links to nearly every chronic disease.

Meanwhile, beef from cows meeting higher welfare standards, such as grazing on pasture in the open air, contains more omega-3s, certain antioxidants, and conjugated linoleic acid—a unique anti-inflammatory fat present in very few foods.

Pastured and free-range chickens, too, produce meat and eggs of significantly greater nutritional quality than low-welfare chickens. This includes higher levels of omega-3 fats, protein, collagen, iron, and zinc in meat, and higher concentrations of vitamin E and vitamin A—as well as a more favorable omega-6 to omega-3 ratio—in eggs. [4] [5] [6] [7]

Even the nutritional content of fruits and vegetables is affected by agricultural practices. Research shows that regenerative farming, with its focus on soil health, produces crops with higher concentrations of phytonutrients, vitamins, and minerals—all of which benefit human health. Conventional farming tends to diminish soil fertility and deplete it of trace minerals, resulting in lower nutritional value and antioxidant capacity among crops.

Animal welfare standards

In an effort to promote higher animal welfare standards, a number of certification and labeling programs have emerged. One of the leaders in this realm is the Global Animal Partnership, or GAP, a nonprofit dedicated to improving the agricultural industry by independently auditing farms and ranking their welfare standards.

GAP uses a multi-tier labeling strategy, ranging from Step 1 (no cages, crates, or crowding) to Step 5+ (animals that spend their entire life on the same farm). The higher the step, the closer the animals’ living conditions are to mimicking a fully natural environment. The fourth step, GAP-4, identifies meat from animals that are raised on pasture year-round, foraging daily in outdoor areas.

In the case of chickens, GAP-4 also means the animals are heritage breeds specifically suited for outdoor living. These birds are slower growing, lower in body weight, and generally significantly healthier than the chickens more commonly used for meat production.

Additionally, many farms and ranches use GAP-equivalent pasture practices and heritage breeds. Some of these farms have their own set of welfare standards, certification programs, and independent auditing. So, while seeing GAP-4 is a great indicator of truly pastured meat, there are plenty of non-GAP-certified farms still committed to the welfare of their animals.

What are we doing about it?

It’s clear that modern industrial farming practices are in dire need of reform. And while the type of large-scale changes necessary will be a long process, we’re committed to doing our part in every way we can.

Currently, “conventional farming” refers to relatively modern practices involving feedlots, synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, intensive tillage, and monoculture production. Essentially, practices that sever food production from the surrounding ecosystem and remove animals from their natural ways of living.

We believe this definition of “conventional” is backwards. Our hope is to help shift the concept of standard farming away from the current destructive, disconnected model that dominates, and back to the holistic systems we previously had in place. We would like to re-normalize what already spent thousands of years being normal.

We utilize the Global Animal Partnership program to constantly improve all of our farm and ranch sourcing, ensuring the greatest possible animal welfare. Wherever possible, we seek out animal products that are either officially GAP-4 certified, or that come from heritage-aligned pastured animals equivalent to GAP-4 standards. This includes:

Chicken: We use GAP-4 chicken meat in all of our chicken-containing soups. Not only are these chickens fully pasture-raised and free from antibiotics, they’re also slow-growth heritage breeds with superior physical health and quality of life. As a result, they produce meat higher in collagen, omega-3 fats, vitamin A, antioxidants, and iron.

Beef: Our Beef Chili is made with GAP-4 beef, while the beef in our soups meets the criteria set forth by the GAP-4 tier: 100% grass-fed, 100% free-range, no feedlots ever, no antibiotics, and no growth stimulants. Responsible grazing enhances the welfare of the cattle, regenerates soil, and improves the flavor and nutrition of the beef.

Gelatin: We use Great Lakes Gelatin, which comes from grass-fed pasture-raised cattle.

Chicken broth: Currently, our chicken broth is free range—meaning it’s made from chickens that are able to roam freely outdoors. However, there’s still room for improvement, and our goal is to eventually source broth that’s at the same level of quality as our meats.

Beef broth: We use broth made from the bones of pasture-raised, grass-fed cattle that are never given hormones or antibiotics.

Where you come in

Although the amount of reform needed to revitalize our farming practices might seem daunting, each and every one of us has the power to plant the seeds of change.

At the end of the day, supply is simply meeting demand. The agricultural industry will continue to provide consumers with the products they ask for—whether that be factory-farmed meat from CAFOs, or high-welfare animal foods from regenerative ranches. The more people who join in asking for foods produced in conscious, responsible, holistic ways, the more those products will populate the shelves.

This means that every choice you make counts. Each time you choose to purchase high-welfare meat, you’re supporting the type of food system reform you want to occur. Each time you seek out products from companies conscious about their global impact, you’re telling businesses: I care that you care. Each time you investigate the source of your food before buying, you’re investing in both your own health and the health of the planet.

Far from a solitary pursuit, every action you take on an individual level unites you with a broader group of people all sharing in the mission to improve this slice of the world. These collective efforts form the very groundwork for transformation.

References

- Reiter K, Bessei W. Gait analysis in laying hens and broilers with and without leg disorders. Equine Vet J Suppl. 1997 May;(23):110-2. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1997.tb05067.x.

- Mughini-Gras L, Enserink R, Friesema I, Heck M, van Duynhoven Y, van Pelt W. Risk factors for human salmonellosis originating from pigs, cattle, broiler chickens and egg laying hens: a combined case-control and source attribution analysis. PLoS One. 2014 Feb 4;9(2):e87933. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087933.

- Hermans D, Pasmans F, Messens W, Martel A, Van Immerseel F, Rasschaert G, Heyndrickx M, Van Deun K, Haesebrouck F. Poultry as a host for the zoonotic pathogen Campylobacter jejuni. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012 Feb;12(2):89-98. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2011.0676.

- Lin CY, Kuo HY, Wan TC. Effect of Free-range Rearing on Meat Composition, Physical Properties and Sensory Evaluation in Taiwan Game Hens. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci. 2014 Jun;27(6):880-5. doi: 10.5713/ajas.2013.13646.

- Ponte PI, Alves SP, Bessa RJ, Ferreira LM, Gama LT, Brás JL, Fontes CM, Prates JA. Influence of pasture intake on the fatty acid composition, and cholesterol, tocopherols, and tocotrienols content in meat from free-range broilers. Poult Sci. 2008 Jan;87(1):80-8. doi: 10.3382/ps.2007-00148.

- Karsten H, Patterson P, Stout R, Crews G. Vitamins A, E and fatty acid composition of the eggs of caged hens and pastured hens. Renew Agric Food Syst. 2010 Jan;25(1):45-54. doi: 10.1017/S1742170509990214.

- da Silva DCF, de Arruda AMV, Gonçalves AA. Quality characteristics of broiler chicken meat from free-range and industrial poultry system for the consumers. J Food Sci Technol. 2017 Jun;54(7):1818-1826. doi: 10.1007/s13197-017-2612-x.